Originally published at: https://geektherapy.org/the-future-of-the-disney-princess/

First published in Thats My Entertainment on April 13, 2017

Author: Ariel Landrum

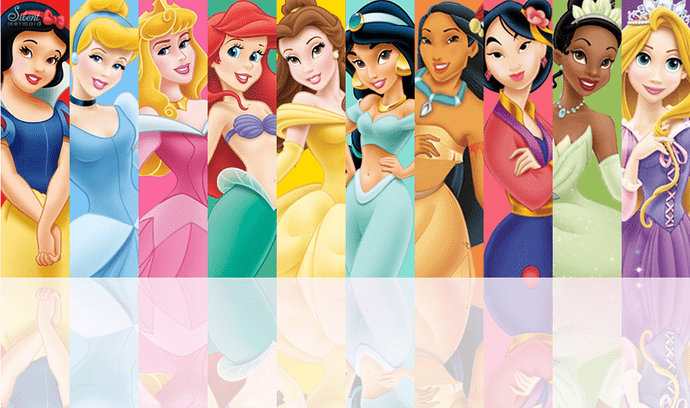

According to Maui in Moana, “You wear a dress and have an animal sidekick; you’re a princess.” The argument around a generic stereotype depicting Disney Princesses has become so pervasive it has even made its way into a few of their films. Disney enthusiasts, who have followed and studied the 80-year legacy of Disney Princess films, have watched it transform from frivolous flights of fancy only fitting for little girls to progressive representations of confident, curious, and courageous heroines. The evolution of these films has charted growth for female heroes.

The advancement of these royals is broken into three waves, “Classic,” “Renaissance,” and “Modern.” Although Disney has attempted to participate in the debate by creating criteria, including having royal lineage (marriage counts), being the primary character in their movie, and being human, they have even deviated from these ground rules. Ultimately, a franchised Disney Princess is created if the character has a crowning ceremony at the park. The most recent was Merida in 2013, becoming the 11th official Disney Princess.

The earliest Disney Princesses, Snow White, Cinderella, and Aurora, could only be described as products of their time. The first feature-length film for the company, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, depicted a young girl (she’s 13 years old in the movie) pining for a prince and turning into a housekeeper for seven grown men (even if they were dwarfs). When matching the story to the time it was created, it not only predated women joining the workforce during World War II, it was commonplace to want a man and live to serve as a woman. Many, however, emphasized how the character was not fleshed-out because the filmmakers focused on the enormous feat of developing a feature-length film.

The next two to arrive on the scene, Cinderella and Aurora, enhanced the convention of damsel in distress. Sleeping Beauty, the epitome of this narrative, features Aurora with only 18 lines of dialogue in an hour-long movie. In Cinderella, audiences are introduced to a woman who can only escape an awful family if she is wed. All three women, products of their circumstances, are not the champions of their own story, do not aid in the defeat of their villain, and continue a female narrative surrounding innocence and helplessness.

After more than 20 years without a princess film, the company began to look to its roots, and a new generation of princesses was introduced; the largest batch yet: Ariel, Belle, Jasmine, Pocahontas, and Mulan. The Little Mermaid provided audiences with a female protagonist who was the first in the legacy to have her independence. She is curious, defiant, and willful, all strengths that became her downfall. It should be noted that these same traits align with prior Disney Princess film villains, all of whom were female, which has led some to believe that the message is independence and power are wrongful traits for a woman. Yet, Ariel spends most of her movie unable to speak, causing her to rely on appearance to achieve her goals. As usual, the villain is defeated by a prince.

The films to follow, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin, Pocahontas, and Mulan, make huge strides in creating independence for their heroines. Belle and Pocahontas embodied independent thinkers who fought against traditional expectations. Although her name means beauty, Belle fought against gender norms by thirsting for reading and dreaming about adventure. Despite the many historical inaccuracies, Pocahontas fought against the cultural norm of arranged marriage. Jasmine also fights against a law that states she must marry, and Mulan impersonates a man to join the military to keep her father safe from the draft. All, however, cannot escape the love-story arc that continues to plague the movies.

As the franchise grows, the new themes adapted into films include princesses actively attempting to rescue an essential character or redeem the villain, increasing the plot for both protagonists and antagonists. In Princess and the Frog, Tiana aims to save Prince Naveen from an eternity as an amphibian. It is debated that she is the first to kill her film’s villain (many cite Fa Mulan from Mulan, but some claim this is false because her spirit animal, Mushu, made the fatal blow). The 3D animated Tangled found Rapunzel sacrificing her freedom to save Flynn. Then as the scene escalates, the villain, Mother Gothel, is pushed out a window, and Rapunzel rushes to save her. This marks the first time a Disney Princess has tried to rescue a villain.

As the Modern Age Disney Princess stories developed, writers started to overthrow the predictable romance. Frozen, which focuses on the bond between sisters, even pokes fun at the love-at-first-sight theme in prior movies, with Hans declaring, “You can’t just marry a man you just met!” This film’s climax differs from its predecessors; instead of a battle scene with a baddy, Anna sacrifices herself to save her sister and the kingdom. Lastly, there is the Pixar Disney movie Brave, which features no love interest. Although the plot focuses on Merida defying her family to avoid taking a husband, she is the first not partnered at the movie’s end.

The culmination of “What is a Princess” starts with frilly dresses and has transformed into courage and spirit in Moana. The story focuses on a bold young lady’s mission to save her people. With the ability to see past the façade of fear around her, she helps liberate Te Fiti, who transformed from a monstrous volcano to an Earth goddess. This movie has no romantic subplot, no prince that saves the day, and challenges the heroine to think critically and act resourcefully, all with compromise and understanding. It appears that the future of the Princess franchise is teaching the next generation that they don’t need to “wait for their prince to come” but instead to face their dragons themselves with real heart and compassion.